Indeed, the 1980s were like that. They were a peak time for ‘gay’ and ‘community’. They were also the time that we got to understand the HIV epidemic, and by the end of the decade its horror. Yet paradoxically for much of the 1980s the HIV epidemic formed the glue that solidified ‘gay’ and ‘community’ and bought us new friends amongst sex works and people who inject drugs – groups then considered to be more at risk of HIV infection. For people with HIV, however, it wasn’t until the end of the decade that we began to be open about our HIV status and to organise.

The first report of something happening occurred in June 1981 when the Centres for Disease Control (CDC) in the USA reported in their publication the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) five cases of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP) amongst gay men. This was followed up by an article in The Lancet documenting Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS) among gay men and a second MMWR report of both KS and PCP amongst gay men. The latter report generated a story in The Sydney Morning Herald describing a ‘gay cancer’. I was involved with a gay radio program on 2XX Canberra and we constructed a lot of hilarity about the notion that cancers had a sexual preference and dismissed the story as trash.

In the middle of 1982 I travelled across North America. I went to a national gay conference in Toronto, Canada. One evening during the conference there was a session at the Hassle Free Clinic on what had become known as ‘GRID’ (gay related immune deficiency). The presenter put up a chart of notifications, which showed them increasing during 1981 and then falling away during 1982. “It could be just like toxic shock syndrome – a small burst of disease which goes away,” the presenter conjectured. The reason for the shape of the graph was a delay in reporting.

In fact, the cases were rising sharply – but the big message was ‘don’t panic’. From there I went to San Francisco for Pride. I remember being transfixed by photographs of KS lesions in a shop window in Castro Street, and on seeing a couple of men with KS in a bar. Visibility makes a big difference – something we had to learn about living with HIV in Australia – and interesting, considering a lot of re-invisibilisation that seems to have occurred this century. Before the parade, I had interviewed a doctor from Bay Area Physicians for the radio program. He had been at a meeting where an epidemiologist involved in tracking the epidemic talked about a cluster of infections in Orange County based on a group of men who had mostly attended the same sex-on-premises venue and had sex with each other. It was the first convincing evidence that ‘GRID’ was a transmissible disease.

I sat there dumbfounded, thinking it was the end of the world as we knew it (words that later became an ‘80s song). Gaetan Dugas, the Canadian flight attendant described as being significant to the early spread of HIV, was not connected to this network, unless by many degrees of separation. He was the first example of victim blaming I remember, a phenomenon that sadly became frequent – and in some places still persists.

I came back to Australia determined to be involved in a response to the looming storm. I moved to Sydney – into a household with four other gay men – one in his mid-20s (my age), and three close to 20. What I didn’t know was that HIV was already spreading rapidly and silently in Sydney. By the early 1990s the three youngest people in the household had died of AIDS. They came out and started being sexual at precisely the time when HIV was spreading, without us being aware of it. It belies all the attempts to categorise and describe people with HIV as somehow ‘bad’ – for many it was just bad luck.

After a period of denial and activism around the blood bank exclusions, gay men started to take what was happening seriously. There were very early campaigns in both Melbourne and Sydney funded by the community. Gay journalism, particularly by Outrage HIV writer Adam Carr, played a significant role in education and overcoming denial. A key article by Adam was published in Outrage in the second half of 1983. Adam described writing the article recently at the 30th Anniversary of the Victorian AIDS Council.

The result was an article 10,400 words long, probably the longest ever to appear in the gay press, which covered the full gamut of what was then known about AIDS. Just to remind you of how long ago this was, I wrote that article with a pen, on paper, and then had to get someone to type it for me. The process of researching that article was for me a journey into a very dark place. I learned that the number of cases was doubling every six months. I learned that the average time from diagnosis to death was less than a year. I learned that the cause of this disease was unknown, and that no one had any idea of how to treat it.

It didn’t take much imagination to see where this was leading. An untreatable disease with a high mortality rate, doubling in numbers every six months was a description of a catastrophe about to happen.

Soon after, attendance at gay venues went down dramatically for a period, the incidence of gonorrhoea and syphilis amongst gay men plummeted, and historical back projections show a rapid decline in the rate of new infections of HIV at this time.

The key interference to HIV’s inexorable spread was taken before any government action. It was these efforts, as well as efforts by sex-worker activists in getting condoms into brothels and injecting drug user activists in establishing world-first needle exchange programs, that prevented a much larger epidemic in Australia

Histories of HIV often make heroes of doctors and governments, and ignore the key role played early in the epidemic by communities at risk – a role that had more impact on diminishing the HIV epidemic in Australia than anything else until the arrival of effective treatments. Indeed, some early state government bureaucrats in NSW actively resisted community prevention efforts. That changed a lot later.

The year 1984 saw the establishment of the AIDS Council of NSW (ACON) – an organisation I was involved with for the next twelve years. I’m not going to focus on ACON in this essay, as I want to get to the beginnings of the organisation of PLWHA (People Living with HIV/AIDS) in Australia.

At ACON’s formation meeting I most remember the first open person with HIV disease. It was prior to HIV testing being available – he had been diagnosed by having a low CD4 count and a set of symptoms that would later be described as ARC or AIDS-related complex. His name was Bruce Belcher, who I knew from Melbourne. I most remember Bruce as a Sister of Perpetual Indulgence walking up Oxford Street – a nun with a full beard. He was approached threateningly by some young Italians, whereupon he raised his voice and said “Hands off sister.” They were so surprised they let him pass. He got up and gave an impassioned please for people with the disease to be significantly involved in the community response. It was a tension between ‘gay’ and ‘HIV’ that persisted for 30 years – HIV was bigger and broader than ‘gay’ and some parts of ‘gay’ felt threatened by it.

It was also when the storm of HIV truly arrived. There were a number of parallel epidemics throughout the 1980s: the epidemic of media sensationalism and bad reporting, the epidemic of highly inappropriate laws (HIL), the epidemic of the dance party, the epidemic of gay bar closures, the epidemic of HIV diagnoses, and towards the end of the decade the epidemic of AIDS and death.

From 1983 onwards AIDS was the new story of the decade – and the next one. Every week there were many media cuttings on HIV. The initial narratives of the media were often victim–blaming. ‘Die, faggot, die’ screamed the headline about a young man who had donated blood, unaware he might have HIV; he’d had sex three times, once with an American. We’d gone from a world where infectious diseases were seen to be mostly solved through antibiotics and vaccinations to a new unknown and deadly disease. Moral panic and blame set in. The stories were endless – sensation and victimisations of an HIV-positive sex worker, the sad story of discrimination of a young girl whose family was effectively forced to move to New Zealand. When treatments started to arrive, the narrative changed to one of ‘breakthroughs’ and ‘potential cures’. We’ve now had a few through breakthroughs and a lot of potential cures.

When HIV antibody testing arrived in 1985, so did notification and transmission laws. The main testing clinic in NSW went from being full one day to empty the next. Compulsory notification laws had been announced. While systems to prevent duplication in epidemiological statistics were indeed necessary, it didn’t have to mean compulsory notification. It led to a huge debate about testing – when there were no treatments, there didn’t seem to be a medical reason to get tested. The second set of laws were transmission laws and often the ‘updating’ of public health acts. These laws were bad in the 1980s – now they are totally counterproductive.

People on treatments were undetectable viral load are the least likely to transmit HIV. These laws discourage testing – and people with HIV who do not know are much more likely to transmit HIV due to higher viral loads. The epidemic of highly inappropriate laws left us with consequences that still persist.

The arrival of AIDS also heralded large changes in gay community and socialisation. If you stood on Taylor Square (a busy intersection in the middle of what was then Sydney’s ‘gay area’) and looked as a map of gay venues you would see more than 60 venues listed. By 1984, you would see less than 15. Many thought HIV caused this, but it was migration to Newtown, a change in investment strategy laws. While gay venues may have declined, gay warehouse parties took off. There was often one or two a week – huge gatherings of tribal celebration. I had many discussions about HIV and coping at these events.

The arrival of testing also resulted in the first wave of the epidemic of known HIV infections. Of the first 1000 tests done in gay clinics in inner Sydney, nearly 50% were HIV-positive. This was close to the San Franciso level. But as more men got tested, the figure approached 15% – the first wave of people tested were those most at risk. In a short period, thousands of men found news of a diagnosis they had to make sense of when there was a lot of conflicting information and a lot not known. Making it harder was discrimination, a hostile environment, a media storm, new inappropriate laws and an ethic of ‘don’t ask, don’t tell.’

It’s hard to get support when you’re not meant to talk to anyone. It was from this period and these experiences that the beginnings of an HIV-positive movement were formed. I got my positive diagnosis soon after this period – and I knew at once that although the rules for our safe-sex culture were defined as ‘assume everybody is HIV-positive’, what we were actually doing was assuming everyone was HIV-negative. Thousands of positive test results changed that, but it was not an easy adjustment, especially as the period started to overlap with the beginnings of a lot more illness and death. AIDS diagnoses start to take off in 1988, and peaked during the 1990s.

The ritual of reading the weekly gay newspaper and opening up to a double page of obituaries began.

In 1986, we got the first news about a potential treatment for AIDS. We heard about a drug where ‘people on their death bed were mowing the lawns the next week.’ It was AZT – and with stories like that it was no wonder that there was a demand for it. The first US trial showed some benefit for people with AIDS and the drug was quickly approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.

The key question was could AZT delay progression to AIDS, if given to people earlier in the course of their HIV disease. By 1988, a trial for people with fewer than 350 CD4 cells was established but there were insufficient places on the trial. We had queues of angry people at ACON seeking help to get a trial place.

The Executive Director of ACON (Bill Wittaker) and President (Ralph Petherbridge) quickly organised the first treatments access demonstration. Although treatments approval and funding were ultimately a federal responsibility, we chose to demonstrate outside the NSW government. It was a real demonstration of how much power we then had – a new infectious life-threatening illness was scary. It’s a power that by and large no longer exists – and as health funding is under threat – it is often now more about illness competition than rational decision-making to allocate available resources.

The demonstration marked the beginning of a long process to reform Australia’s drug approval and regulation systems. State funding was a temporary fix – the real problem lay in Australia’s arcane and out-of-date drug regulation system, which did not give priority to people with life-threatening illnesses and delayed approval for years so that any problems would be known overseas first. My role changed from preventive education to treatments education and access.

The promise of AZT was ultimately a let-down. At the doses used, it produced considerable side-effect problems. And for most mono-therapy (single drug) treatment regimes, HIV was able to quickly develop resistance. Drug companies needed to work together to develop combination treatments – something they were very resistant to do.

Sadly, drug companies did not learn the lessons of cooperation, as can be seen in Hepatitis C where a treatments revolution is under way at long last. Treatments access; education; approval regulation and reform; and ensuring expanded and early access while trials occurred and importing overseas drugs via a buyers’ club became a big agenda for the community sector and overlapped with the birth of the PLWHA movement.

The Third National Conference on AIDS was held in Hobart in 1988. Some brave PLWHA wore badges saying ‘talk with us, not about us’. At one point, Terry Giblett (an openly HIV-positive man) asked people with HIV to take to the stage. We suddenly discovered that 50% of the staff at ACON at the time were HIV-positive. It was a scary moment.

There were a number of key people in the emergence of the PLWHA movement in NSW: amongst whom were Robert Ariss, Andrew Morgan, Gerald Lawrence, Paul Young, Amelia Tyler and Vivienne Munro. There were many more but I most remember the names I’ve listed. Paul Young became the first HIV-positive media person in NSW. In my opinion, it took a lot of guts in that environment. Out of the new activism a lot of things occurred.

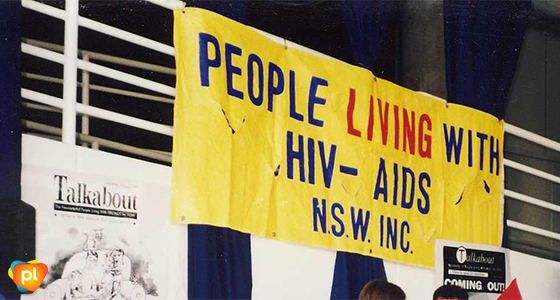

PLWA (NSW) – later PLWHA (NSW) and now Positive Life – was formed and a major project – the HIV Support Project – was established. During the years 1989 to 1996 it saw about one-third of people with HIV in NSW and trained over 500 facilitators. Half of whom died during those years; the toll of being in the epicentre was very large.

Because positive organisations were established after the big increase in community-based organisations, they were often the poor cousins and not adequately resourced. Governments preferred not to deal with extra organisations, abut for people with HIV the need for our won organisation was clear. Sadly, the funding disparity was often never properly fixed.

At the formation meeting of PLWHA (NSW) the biggest debate was whether people had to be open about their HIV status in order to be full members. It was a reflection of the stigma at the time – and led to a national HIV stigma campaign where a number of brave PLWHA feature openly in TV and print advertisements.

As the 1980s ended, death rates were skyrocketing. HIV sero-conversions had returned, often fuelled by the increased viral load of people whose illness was advancing. Treatments were still mostly mono-therapy and had a lot of drug-limiting side effects. Treatments activism had been born and the PLWHA movement had begun, which played a huge role in the dramatic changes that occurred during the 1990s.

And my choice of songs changed from ‘It’s the end of the world as we know it’ to ‘Things can only get better’. They did – but there’s a memory we all carry that many of us struggle with.

1990

Ross Duffin

Ross was ACON’s first education manager and worked in the HIV sector until the mid-90s.

Through Our Eyes: Thirty years of people living with HIV responding to the HIV and AIDS epidemics in Australia, John Rule (Editor), p 22-27, published by the National Association of People with HIV Australia (NAPWHA) 2014.

Published for Talkabout Online #190 – March 2018